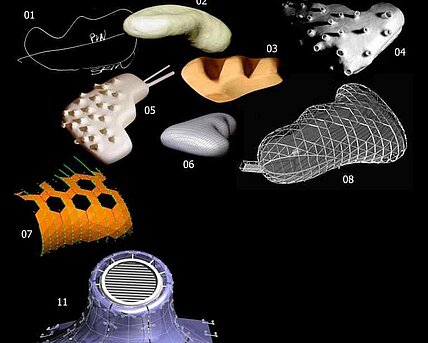

The Kunsthaus has been called a baby hippo, sea slug, porcupine, whale and a "Friendly Alien" - this last name having been coined by Colin Fournier, one of its two architects. For him, the Kunsthaus is a biomorphic, indefinable something, a hybrid, strange and familiar at the same time, with the "charm of a friendly mixed-breed stray dog, definitely highly questionable in terms of pedigree."

Architecture

Architecture

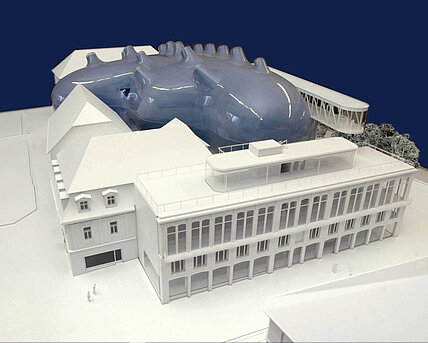

The Kunsthaus was built as part of the programme for the European Capital of Culture 2003 - a new architectural landmark in Graz that has come to be mentioned in the same breath as the city's iconic clocktower and the Schlossberg. Each year it attracts many thousands of visitors from all over the world, and has long since been absorbed into the urban identity of the city. Designed at the beginning of the millennium by architects Peter Cook and Colin Fournier, its unique shape and striking colour inspire and thrill those who encounter it. In the evening, the Kunsthaus communicates with its urban surroundings through the BIX media façade designed by realities:united.

The building is situated in a less privileged district of the city, opposite the historic city centre. It was built on a vacant lot between Lendkai and Mariahilferstraße, directly adjoining the ‘Eiserne Haus’ (Iron House). Once a modern department store built by the architect Josef Benedikt Withalm from 1846–48, the building was gutted and linked to the Kunsthaus. The listed façade and its cast-iron structure on the upper storey were preserved. The arrival of the Kunsthaus Graz meant that the area around the Südtiroler Platz was upgraded and connected to the old town of Graz. Since then, many small shops and restaurants have been set up, and a creative scene is developing.

Image Credits

Exhibition Facilities

The very first considerations of the spatial programme at the Kunsthaus were already based on the idea of "platforms" that should be flexible, adaptable and fluid. As with the design for the Monte Carlo Bâtiment Public of 1973, the first joint venture between Cook and Fournier, architecture was designed to extract specificity from various "events", a "feature-space", a space with special features, a platform for a wide range of activities.

As a transdisciplinary exhibition, action and mediation centre for contemporary art in all forms of media and with a total usable area of 11,100 m2, the Kunsthaus Graz has a differentiated spatial and functional programme. While the interior of the building as a "black box of hidden possibilities" (Colin Fournier) to encourage the curators to new uses of space, its outer skin is playable as a media façade. The Kunsthaus café, shop and underground parking with 146 parking spaces complete the offer for the visitors.