Climate change, wars, political upheavals – we are living in a time of growing uncertainty. The exhibition Unseen Futures to Come explores how we deal with this and what meaning we can find in it.

Unseen Futures to Come. Fall

Image Credits

How do we find orientation in a world full of crises?

Philosopher Federico Campagna explores how our understanding of the world shifts over time. Using the metaphor of a symbolic library based on the rhythm of the seasons, he shows how our perception of reality changes—shaped by historical context, ways of thinking, and lived experience.

Dana Awartani . Federico Campagna . Christoph Grill . Adelita Husni Bey . Marija Marković . Vladimir Nikolić . Yhonnie Scarce . Andrej Škufca . Jože Tisnikar . Sophie Utikal . Bill Viola . zweintopf

Show all

Works in the Exhibition

Image Credits

Dana Awartani

I went away and forgot you. A while ago I remembered. I remembered I’d forgotten you. I was dreaming, 2017, Mixed-Media-Installation

Over a number of days, Dana Awartani meticulously created an immaculate geometric floor design from sand in a house in Jeddah. The video shows how, within a few minutes, she very deliberately sweeps the work away again. The destruction of the artwork is a commentary on the careless treatment of cultural heritage and identity by a society obsessed with modernisation. As the work is destroyed slowly, almost meditatively, we are given time to reflect on our own actions.

The sand was dyed by the Saudi Arabian-Palestinian artist with natural, locally sourced pigments, and the pattern is inspired by traditional Islamic floor tiles. Their geometric patterns were once common in Arab houses. Awartani scattered the work over the floor of an abandoned house in Al-Balad, the old town of Jeddah, where her grandparents’ generation once lived. As one of the first buildings constructed in the ‘European style’, it is an example representing the shift away from traditional Hejazi architecture, which had evolved over centuries based on regional materials and climatic requirements, and towards a westernised building style. Due to the growing influence of the West during the 1950s and 60s, a strong desire for modernisation emerged among the social elites of the Arab world. All that was western was regarded as ‘developed’ and ‘civilised’, whereas their own cultural identity was almost entirely given up.

In the duality of the creation and destruction of the fragile, ephemeral sand art, Awartani aims, as she does in many of her works, to raise awareness of the preservation and appreciation of our cultural heritage – not as an attack on modernisation but instead as a vision of how the old and new, the past and present can co-exist on equal terms. Her paintings, sculptures, performances and multimedia installations combine a contemporary understanding of culture with the sustainability of craft techniques and local materials, often in the form of reinterpreted geometric patterns that reflect the harmonious symbiosis of mathematics, nature, spirituality and beauty in Islamic art. This desire for coexistence is also reflected in the work’s title, which comes from a poem by Mahmoud Darwish. The contemporary Palestinian poet’s work explores exile and dispossession, loss and grief, but also rejects any nationalist construction of identity, preferring a life-affirming simultaneity of beauty and melancholy, despite the most difficult of circumstances.

Image Credits

Federico Campagna

Fall: A Library of Twilight Worlds, 2025, 250 books

Federico Campagna is a philosopher and writer who engages with metaphysical questions on the ethical challenges of our society. He explores how we think and construct reality, and juxtaposes technical perception with a more imaginative dimension of thinking. He continues to contribute to debates around the limits of modernity, the crisis of meaning and the philosophical possibilities for alternative futures.

For the exhibition he has conceived a library titled Fall: A Library of Twilight Worlds. This is a collection of 250 theoretical and philosophical books structured around the metaphor of the seasons, which symbolise our approach to and perception of the world. Focusing on the season of autumn/fall, he interprets this as the season in which certainty dissolves, knowledge is questioned, and fear of the unknown intensifies. Here, rational thought meets alternative worldviews, scientific texts stand alongside occult and esoteric writings – so highlighting the complex interplay between reason and uncertainty in times of upheaval.

Campagna states: ‘In most cases, however, as the old background starts to crumble, a new one is ready behind it to take its place. The moment of passage between them is always disconcerting, but the shock that accompanies it, has usually more to do with the difficult adjustments that we must make to the characters, rather than with the glimpse at the empty backstage behind them.’[1]

Image Credits

Christoph Grill

The Roar of the Sea and the Darkness, 2025

In his pictures, photographer and archaeozoologist Christoph Grill explores the layers of meaning in these natural and anthropogenic landscapes, examining how they are inscribed and overlaid with the traces of past events. He travels across the landscapes, always open to stories and encounters, guided by what he finds along the way. This approach is reflected in his photos: the images do not direct our gaze but instead allow it to wander, to set out on a journey of discovery, to chance upon seemingly incidental details. Much in the spirit of Susan Sontag, Grill shows us what already exists as an image – without interpreting what he sees.

And yet, on the other hand, he also engages in an intense examination of the context and situation of the landscapes he photographs. Captured over the course of ten years while he travelled through the successor states of the Soviet Union, these photos take us with him into contaminated landscapes. He explores the ‘massive disturbances of political ideologies and capitalist extractivism’ (Astrid Kury), finding in them the starting point for socio-political, ecological and existential questions. He does not remain with the dystopian, however, but shows the vulnerability and resilience of both humans and nature. The series title is borrowed from a cycle of poems by the British writer Malcolm Lowry, whose texts often address the search for identity and the allure of distant places, so emphasising this productive contradiction in Grill’s work.

In his essentially unsentimental images, Grill creates poetic yet ambivalent and timeless places of longing. He does not reproduce stereotypical motifs or illustrate familiar narratives; instead, he works through allusion. He draws our gaze towards the incidental rather than the recognisable, offers irritation rather than explanation, and so allows our own imaginations to put together stories that may or perhaps may not have happened.

Image Credits

Adelita Husni

Bey Briganti, 2023, Print

I Briganti are an anti-fascist and anti-racist rugby club in Librino, a district on the outskirts of Catania in Sicily. The neighbourhood was built in the 1970s as part of the gentrification of the city centre and has suffered decades of institutional neglect. The I Briganti club began rugby training for young people from Librino in 2006, and in 2012 occupied the then vacant San Teodoro sports complex.

Attack and defence, territory, anti-fascism. These ideas and how they are inscribed in and shape the territory that members of the Junior women’s rugby team inhabit are at the heart of Libyan-Italian artist and pedagogue Adelita Husni Bey’s photos. Her process-based works portray analyses of shared social realities. These are developed with different participants in collaborative workshops based on holistic pedagogy. Her focus on the collective is deliberately contrasted with the increased individuality and isolation of capitalism, while also challenging the ‘currency’ of authorship.

For Briganti she invited the team to an Image Theatre workshop where they engaged with the club’s history in the socio-political context of Librino. Based on conversations and interviews carried out over a number of months, the photos were then produced in two intensive workshops.

Following a short discussion about a concept, participants form an image piece by piece. Without coordinating or planning, they enter the predetermined image space one after another and take up a position there. Instinctively, inspired by those who have entered and positioned themselves before them, they find their place and take up their role in the image. After Husni Bey has photographed the resulting tableau vivant (living picture), the participants talk about how events and memories have been expressed in the individual and collective body.

How does attack work in rugby? And how did it manifest itself in social reality when the club was repeatedly attacked by far-right extremist groups? What is it that we are defending when we stay after practice in the sports hall to guard against arson attacks? Will we stay in our neighbourhood even when many others are leaving, and we also feel like we want to leave? Husni Bey’s artistic and social/educational work reveals complex social contexts and highlights one’s own close involvement in them – for us as viewers just as much as for the protagonists.

Image Credits

Marija Marković

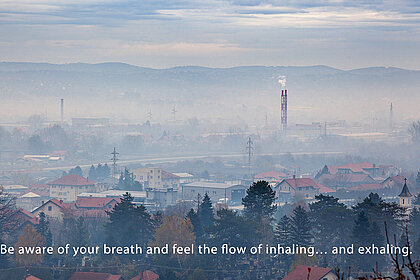

I Want You to Panic, 2021, Video

The minimum heart rate during a panic attack is 120 beats per minute. Marija Marković presents 120 images per minute that show the disastrous ecological effects of human activities on the Earth. The pictures were gathered by activists from areas with high air pollution all over Serbia. The calm voice from off screen only appears to subdue the hectic breathlessness of the rapid sequence of images, guiding us through an exercise intended to help control our breathing and regain a sense of safety during a panic attack.

Spanning various mediums, the artist and activist’s oeuvre explores how we tackle the crises of our age and seeks primarily to raise awareness of ecological issues and their urgency. Her most recent work examines the social, physical and psychological impact of climate change. Its repercussions and the apparent helplessness with which we as individuals face them can cause feelings of fear and panic. Our excessive consumption within almost entirely uncontrolled global neoliberalism is pushing the natural capacity of the planet to its limits. The air we breathe is getting thinner and thinner. Whose is the air we pollute, whose is the environment we are destroying? Marković sees the irreconcilable conflict between unbridled individualism and the need for intergenerational social responsibility emerging with increasing clarity. The private sector maximises profits for the few and enhances the comfort of a relatively small group of people, and in doing so undermines society’s efforts to use our existing resources in a sustainable way. From all sides comes reassurance (that action will soon be taken and that it will be enough) while we end up reassuring ourselves (that it won’t be so bad after all). But does this calmness help us to act responsibly, or is it instead a deceptive calm that is lulling us into political passivity?

Marković borrowed the title of the work from climate activist Greta Thunberg. In her speech to the European Parliament in 2019, she demanded: ‘I want you to panic. I want you to act as if your house was on fire.’ A clear, almost desperate call from the next generation for us to finally take action.

Image Credits

Vladimir Nikolić

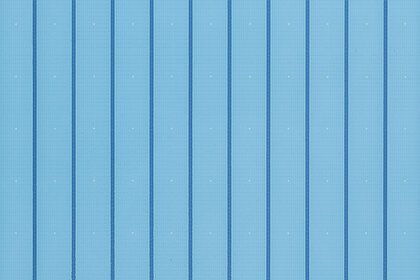

800m, 2019, Single-channel 4K video

Vladimir Nikolić is an artist whose work frequently addresses the cultural and ideological transitions of contemporary society, exploring how these shifts are shaped – and reshaped – by technology, image-making and the evolving role of art itself. Central to his practice is a sustained interest in the mechanisms of human perception. As he said in an interview: ‘Perception is not a reflection of reality, but an interpretation of it.’ For Nikolić, technology plays a decisive role in shaping how reality is constructed: not simply as a neutral tool, but as an active organiser of visual experience.

This conceptual framework is realised in his work 800m, part of the Serbian national presentation at the 59th Venice Biennale, titled Walking With Water. The installation reflects Nikolić’s ongoing interest in the interplay between image, illusion and interpretation, and the subtle ways in which technology conditions our understanding of the world.

The intertwining of technology with our view of the world and, at the same time, the way we perceive it is reflected in the choice of medium and how the work is presented. The portrait orientation of the video initially deceives us: from a distance we think we are looking at an abstract minimalist painting. Only as we draw closer do we realise that the image is not still. A person, tiny in comparison to the size of the whole screen, is swimming lengths of a pool.

The title 800m comes from the fact that the artist’s original plan to swim 1000 metres failed because his memory card filled up during filming, so that only 800 metres was recorded. This play on our perception reveals the artist’s fundamental interest in images, which he does not take for granted, but always sees as influenced by context.

Ultimately, 800m encapsulates Nikolić’s broader investigation into how images are produced, received and contextualised. He challenges us not to take what we see at face value, but to consider how deeply our perceptions are mediated, filtered and framed – not just by technology, but by the cultural and conceptual lenses we bring to the act of looking.

Image Credits

Yhonnie Scarce

Operation Buffalo, 2024, Installation

Yhonnie Scarce is an Australian artist and a descendant of the Kokatha and Nukunu peoples. Her work addresses the trauma and legacy of Australia’s colonial past, focusing on the displacement, cultural erasure and systemic injustices experienced by Aboriginal communities. She works primarily in glass, which holds symbolic weight in her work. Glass emerges in the process of subjecting quartz sand to extreme heat.

Scarce handcrafts glass objects and sculptures. In large spatial installations, including the work shown here, Operation Buffalo, she refers to the nuclear tests carried out by Great Britain in Australia during the 1950s. The tests took place on land that traditionally belonged to the Aboriginal people, who were forcibly displaced, further contributing to the destruction of their culture. The toxic fallout and radiation spread much further than planned, exposing many people to radiation, including those who had worked on the tests and residents living near the test sites. Both veterans and Aboriginal people died younger from cancer and leukaemia, while their descendants also suffered the consequences. The test site was inaccessible for more than 30 years. Reports on the effects of nuclear testing in that area on humans, animals and the environment vary widely; it was not until the 1980s that the extent of the contamination began to be discovered. The long fight for clean-up, recognition and reparations has only partially addressed these injustices.

The installation Operation Buffalo consists of 1,300 glass objects resembling Australian yams – a traditional Aboriginal food source. It functions both as a memorial and a warning, but also as a tribute to human resilience. It acknowledges the deep scars of nuclear colonialism while urging ongoing vigilance against the repetition of such violence. Through the medium of glass – both beautiful and brittle – Scarce offers a stark yet poetic examination of Australia’s silenced histories.

The project by artist Yhonnie Scarce was shown with the support of the Australian Embassy.

Image Credits

Andrej Škufca

Black Market: 6GB ending, 2020

Andrej Škufca’s artistic practice explores speculative perspectives on the future, particularly those that invite reflection on posthuman or techno-organic hybrid systems or entities. Acknowledging the difficulty of articulating concrete projections of the future, Škufca employs associative techniques and references that simply propose possible scenarios.

The sculpture 6GB ending is part of Škufca’s broader series Black Market. Traditionally, the black market refers to an unofficial economy that exists outside legal structures, often flourishing during periods of systemic breakdown or crisis. In the context of high capitalism today, this metaphor takes on a new significance. The market as such is no longer just an economic system – it is a totalising mechanism that defines relationships between people, other species and the natural world. In its most extreme form, capitalism drains and depletes all resources – human, animal, ecological – for the sake of maximum profit. With that totalising market, a question arises: is there still a distinction between the black market and the global market in a conceptual sense, since the exploitation of resources seems to ignore juridical and, above all, ethical laws?

The title of the sculpture, 6GB ending, alludes to Frank Stella’s 1960 painting Six Mile Bottom, a minimalist work characterised by disciplined, repetitive shapes. Stella’s work comments on the increasingly mechanised and alienated condition of modern life, employing parallel lines to create a geometric image that gives a sense of endless expansion as well as contraction.

Made of inorganic material, Black Market: 6GB ending has a surface reminiscent of a lacquered car body. At the same time, the sculpture recalls the organic forms associated with early organisms and mycelial structures, so intertwining different temporalities and hybrid forms in its very materiality. Similar to Frank Stella’s painting, the extending arms and their interconnectedness evoke a feeling of stretching and shrinking into infinity. There is a deliberate ambivalence in the sculpture’s posture. Its outstretched, interlacing arms may be interpreted as reaching, growing or invading. Is this form threatening, or is it offering a new way of being?

Škufca’s work embodies the aesthetic of collapse and the possibility of emergence. It invites us not to predict the future, but rather to sit within its uncertainty, and to consider that in the ruins of one system, new hybrid life forms – technological, biological, economic – are already taking shape.

Image Credits

Jože Tisnikar

Love, (LJUBEZEN), 1977, Oil on canvas

Jože Tisnikar (1928–1998) stands as one of the most significant Slovenian painters of the second half of the 20th century – and unquestionably the most important self-taught artist of his generation. His work is defined by an engagement with the existential themes of death and life, articulated through iconographic visual language.

Tisnikar’s singular vision was shaped by his intimate proximity to death. For many years, he worked as an assistant in the morgue of the Slovenj Gradec hospital, where he was confronted daily with the physical and emotional realities of mortality. These experiences left a deep mark on his psyche and found direct expression in his paintings. His work is difficult to assign to a particular art movement; Slovenian art historian Tomaž Brejc has placed it in the category of dark modernism.

His oeuvre is primarily characterised by images of the dead, the apocalypse and delirium. Motifs of ravens and crickets often feature in his paintings, symbolising the premonition or even constant presence of death. Love depicts an embracing couple – however, like many of Tisnikar’s works, it too includes a cricket, which, although placed in the background, looms disproportionately large and menacing. On a symbolic level, the painting can be understood as implying that death will always triumph over love, or that the awareness of our own mortality emphasises the importance of love and that it is what makes us, as humans, capable of love.

Ultimately, Tisnikar’s work demands reflection on what it means to be human. His paintings are confrontations with the emotional and metaphysical limits of existence. In a world increasingly distanced from death, he forces us to look directly at it – and in doing so, perhaps also at the depth of our own capacity for love.

Image Credits

Sophie Utikal

I Thought We Had More Time, 2021, Textile

Sophie Utikal’s triptych immerses us in a fantastical, dreamlike world peopled by faceless female bodies. Within an ambivalent and at times dystopian atmosphere, these beings float through the surrounding waters, interlinked in a shared destiny and responsibility –

the responsibility for a changing and threatened world.

Utikal’s vivid patchworks made from textile fragments draw on the tradition of arpillera, familiar to her from her mother’s South American family. They can be read as expanded self-portraits. In her work she starts from her own body, but goes beyond herself to explore social issues such as migration experience, multiple nationality and the resulting contradictions. Traces of social violations and isolation are transformed into self-confident and self-empowering images. She sews the separately produced elements with rough stitches, piecing them together with black thread in both a real and figurative sense.

In the last few years she has focused on our shared responsibility for the planet. In a poetic and symbolic visual language, I Thought We Had More Time establishes a future scenario: Utikal responds to the impact of climate change produced by humans, which has been known for a long time now, and yet has only recently become anchored in the collective consciousness – the melting of the glaciers, extreme drought and rainfall, the poisoning of the seas and the extinction of species. She examines practices of care and devises imaginary transformations of life towards a coexistence between species. From the perspective of Women of Colour she illuminates concepts of togetherness and resilience in times of climate crisis and other disasters.

Most importantly, the triptych is a vital reminder that the age of the human species in this current form will come to an end. In the face of climate catastrophe, it is increasingly clear that in all issues of social discrimination, including those present in Utikal’s life and work – which are far from incidental – the existential question of biological survival must be a central consideration. Changes far more radical than we can currently envisage will be needed to deal with these challenges.

Image Credits

Bill Viola

The Raft, 2004, Video and sound installation

Bill Viola (1951–2024) was an American video artist who was deeply immersed in questions of the human condition, dealing with such fundamental themes of our existence as life, birth and human transience. He belonged to a generation of artists who, in the early 1970s, began an intense engagement with video not just as a tool for documentation, but as a medium that would open up new possibilities and forms of expression for their ideas. The scope of his work ranges from videos to spatial installations and objects.

His video installations – often large-scale, slow-moving and intensely emotional – invite the viewer into a meditative space. References to iconic works of art, historical frescoes and paintings are often found in his videos. One of his greatest inspirations was Michelangelo, whose influence can be seen in the specific aesthetic language used by Viola. His slowing down of the videos is like an investigative lens that allows us to look more deeply into how human emotions are expressed, processed and transcended – and how they can be rendered in time-based media.

Viola’s work also resonated outside the art context: he created The Raft for the 2004 Olympic Games in Greece. The video is named after Romantic painter Théodore Géricault’s famous picture The Raft of the Medusa (1818-19), an icon of French Romanticism. This enormous painting (490 × 716 cm) depicts a raft on which a few people have taken refuge, a handful of survivors left after the ship Medusa sinks off the coast of Mauritania in 1816.

As the title suggests, Viola draws on this painting as a reference for his work. The latter depicts a group of people surprised by a powerful jet of water directed at them from all sides. Just as the water begins to crash over the group without warning, after a while it also stops abruptly, and those who have been knocked to the ground by its force attempt to stand up. It seems that the water has also washed away any class distinctions we may have detected earlier from how they were dressed. Under shock, they all try to help each other back to their feet.

The video reflects the contemporary situation of living under the constant threat of disaster, while at the same time speaking of an immense faith in humanity and resilience.

Image Credits

zweintopf

2406079: Road to Nowhere, 2012/2025, Photo wallpaper

A road to nowhere: a cliché par excellence. A cloudless blue sky above a long straight road: infinity, freedom, a media icon reproduced countless times in film, television and advertising. It is a motif that is used especially often in advertisements selling cars, since they – more than any other object in our individualistic consumer society – stand for freedom. And yet most cars will rarely drive along such endless highways, but instead spend most of their existence standing in a car park or staring at a blank concrete wall in a parking garage. Where, thanks to zweintopf, they can – temporarily at least – experience the place of their dreams.

Founded in 2006 by Eva Pichler and Gerhard Pichler, the artist duo zweintopf work both as artists and curators in classical exhibition contexts and in (mostly unannounced) site-specific art interventions in public space. They work in various media and conceptual artworks to engage with the sociopolitical issues around consumption, public space and urbanity, exploring their inherent everyday aspects of absurdity. At the core of zweintopf's oeuvre is their process of discovering the codes and symbols of these with a keen sense of observation, then condensing and transforming them into art interventions or works through their distinctive poetry of trivial things.

Here they address the automobile (or rather auto-non-mobile) contradiction between yearning and reality. 2406079 is the product number of a photo wallpaper available on the internet – an off-the-peg place of desire. zweintopf turned this wallpaper, designed for private living rooms, into a trompe-l’oeil for the parking garage of a Graz shopping centre. A standardised road led from a parking space, along an exact extension of the floor markings, to the nowhere of the concrete wall. The guerrilla wallpapering action was captured on video and in photographs.

For the Kunsthaus Graz, zweintopf has printed the photo of the completed action as a photo wallpaper, multiplied in a theoretically endless game with the ‘visual spatialisation tool of wallpaper’ (zweintopf) as a simple illusion, so that the Road to Nowhere extends the Travelator leading from the urban foyer up into the exhibition space.