Peter Gerwin Hoffmann

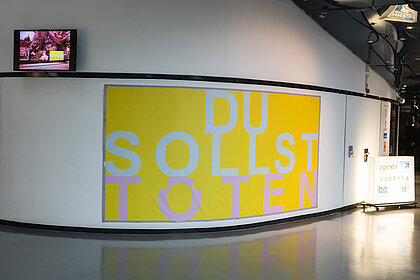

Du sollst töten

Image Credits

Duration

02.10. - 10.11.2024

Opening

01.10.2024 18:00

Location

Kunsthaus Graz, Foyer

Show all

About the

Exhibition

war is our way of life, our opponent is our fellow man and the world with all its beings.

we will win! (Peter Gerwin Hoffmann)

Peter Gerwin Hoffmann, an early representative of Austrian media art, has been working continuously in electronic and social space for many years. His engagement with the subject of war has also been going on for a long time. In early works, in which Hoffmann still chose painting as a form of artistic expression, this can be seen, for example, in pictures on the Middle East conflict; years later, in the early 1990s, he presented the wars in the former Yugoslavia as media wars in an impressive installation in public space in Innsbruck on Landhausplatz with the Freedom Monument: Every day during the evening news, passers-by triggered the sound of a grenade being launched, flying and hitting the ground, while TV logos flashed and screens flickered. Because wars are – also – fought through and for the media, Hoffmann makes clear in this work. A message that he takes up again in Du sollst töten (Thou shalt kill) and combines with an urgent plea for peace research: Despite our great good fortune to have been able to live in peace for so long, politics and civil society have failed to promote and research peaceful conflict resolution. With his project, Peter Gerwin Hoffmann wants to draw attention to this gap and to the fact that arms production has lobbyists behind it, while there is (apparently) no money to be made from peace research.

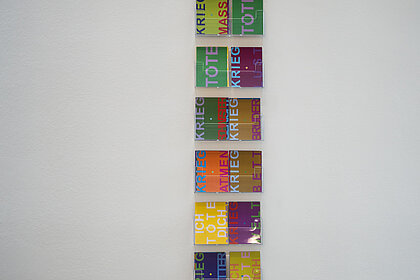

Du sollst töten is a multi-part installation consisting of a large banner of the kind that is hung on the perimeter boards of sports grounds at sporting events for advertising purposes, a series of postcards to take away and a video showing the television broadcast of the coronation of King Charles and Queen Camilla. The staging of the military at the coronation of the British royal couple with colourful uniforms and beautiful weapons is reminiscent of the cast of a light-hearted operetta. The bayonet, from the tip of which blood could drip, is suppressed in everyday perception. The banner and postcards use bright colours and short slogans to promote killing and war: DU TÖTE DU (YOU KILL YOU) – KRIEG – SCHÖN (WAR - BEAUTIFUL) – MICH TÖTE NICHT (DON’T KILL ME) – KRIEG - EHRE (WAR - HONOUR) etc. The trivialisation of death that Hoffmann addresses is contrasted with the incomprehensibility of the consequences, namely the total extinction of one’s own life and/or the lives of others. The artist is interested in the individual soldier, whose duty it is to accept dying as a possibility and to have no alternative to killing.

Regardless of which armed conflict is involved (the multitude of flags that end the coronation video in a single flicker and are also found on the postcards show the universality of Hoffmann’s statement) - there is no such thing as a ‘just war’, even if our respective media bubble suggests the opposite. Du sollst töten is a plea for peace, a cry for help that is made on behalf of all soldiers who have been and are being sent to war. And it is an appeal to break out of the constant loop of ‘doomscrolling’ and devote ourselves to constructive solutions instead of sinking into images of catastrophe and hopelessness.

Image Credits

Image Credits

Image Credits

Image Credits

Image Credits

Image Credits

Image Credits

Image Credits

Image Credits

Image Credits

Image Credits

Image Credits

Image Credits

Image Credits

Image Credits

Image Credits

Image Credits

Image Credits