Nothing is so typical for Renaissance art as the world of ancient gods and heroes. Italy is the classic soil of ancient culture. Finds of Roman statues turn into sensations, princes, clerics and patricians become collectors. The Renaissance is also making its way into the north. From there throngs of artists head towards Italy to perfect their skills there.

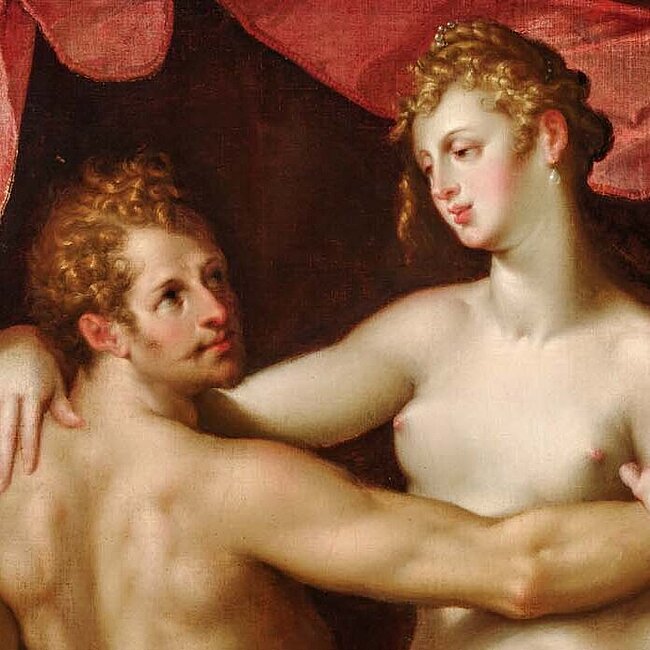

Art conveys complex thoughts as never before at a high intellectual level. Ancient figures are ideal for this. The more complicated the content of an artwork is, the more it is appreciated. Such complex programmes give both artists and clients the opportunity to demonstrate their own education and competence. Erotic scenes warrant particular applause. They flatter the eye of the connoisseur. Painters often take classical themes on the occasion, to prove their skills with sophisticated nude studies.